In an effort to be less stupid, or to prove to myself that my brain might still be able to process complex thought, I am re-reading Gaston Bachelard, albeit very slowly, in small gulps over weekends. The Poetics of Space has got my wheels spinning about creating a home and specifically a home for small children.

The book was published in 1958 and is a very strange, dense, lyrical text, in which Bachelard sets out to explore the affect of architecture on our imaginations—especially the poetic imagination and work of image-making.

In The Poetics of Space, he examines the images and meanings conveyed by wardrobes, nests, shells, corners, attics, and so forth, with a liberal sprinkling of poems from Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Rilke, Milosz, and others to illustrate the conceits. The chapters do not seem to follow any discernible pattern or structure, and I wonder why Bachelard chose the images he did. It is best, I think, to be carried along by his charming, playful prose (so unlike the archetype of the self-serious philosopher) and not ask too many questions.

But Bachelard is indeed a philosopher and phenomenologist—not a Montessori teacher or a child psychologist. Accordingly, he brings a detached, theoretical French mind to homemaking. In other words, he’s not writing a mommy manual. But by golly, I’m going to make it one.

Some of his primary claims include the following, and I am interested in applying them to our home.

Childhood is more real that reality

What does Bachelard mean by this? Only God knows, but I think he is getting at how formational childhood is to our unconscious selves. He writes (emphasis added):

“The positivity of psychological history and geography cannot serve as a touchstone for determining the real being of our childhood, for childhood is certainly greater than reality. In order to sense, across the years, our attachment for the house we were born in, dream is more powerful than thought. It is our unconscious force that crystallizes our remotest memories.”

External facts about the town or home we grew up in don’t actually dictate how our minds are shaped; it is the experience of the house itself, and our dreams in it and about it, that make our imaginations what they are today.

Children must feel safe and sheltered at home

“For our house is our corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word.”

Maslow’s hierarchy and all that, but this is an obvious starting place. Home is supposed to be a safe place, a space of refuge. If it’s not, everything else in the child’s life and mind starts to crumble. My heart breaks when I think about children who are experiencing homelessness or housing instability and how significant this loss is to their development. It is a loss that cannot be understated.

This vital need, for home to be a haven, has more to do with the people inhabiting the space with the child than with the architecture of the space itself, but if there is a faulty roof or a drafty room or an infested basement or a permeable front door, a child’s sense of safety is diminished. In an unsafe home, the imagination cannot develop naturally, Bachelard attests.

Children should find inspiration at home

Beyond shelter, homes should be places that nurture children’s creativity, inspiration, and dreams. This is, of course, easier said than done, but it makes me think very carefully about how I set up rooms: the furniture I choose, the art I select, the spaces I arrange and maintain. How do these spaces allow children to explore? (A recent purchase, copying our friends the Bushes, who really know how to make a beautiful, child-friendly home: the Nugget, which has already been extremely well-loved and used in its new home in our family room.)

“It is on the plane of the daydream and not on that of facts that childhood remains alive and poetically useful within us. Through this permanent childhood, we maintain the poetry of the past. To inhabit oneirically the house we were born in means more than to inhabit it in memory; it means living in this house that is gone, the way we used to dream in it.”

All of this sets the stage for the following point.

Children need to be given space to be “bored” in their homes

We don’t like to use this word “bored,” but what Bachelard means is empty, unstructured time at home. Time in which no one is telling the child what to do or where to be or how to act. Without this kind of time, children do not ever get to fully use their imaginations at home.

We are not good at doing this yet with Moses. He expects one of us to be doing an activity with him all the time. It’s exhausting for us, frankly, and I don’t think it’s helpful for him. I think a key, for us, is to be busy with other household tasks and leave Moses to his own devices. We are not there, in other words, to entertain him. Fellow parents of little children, any tips?

Our childhood homes are the foundation of our imaginations

“Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.”

Much of the first chapters of the book are about the power of nostalgia—and the memories of our childhood homes—as the foundation of our poetic imaginations. Without this foundation, Bachelard claims, we would have no imagination at all.

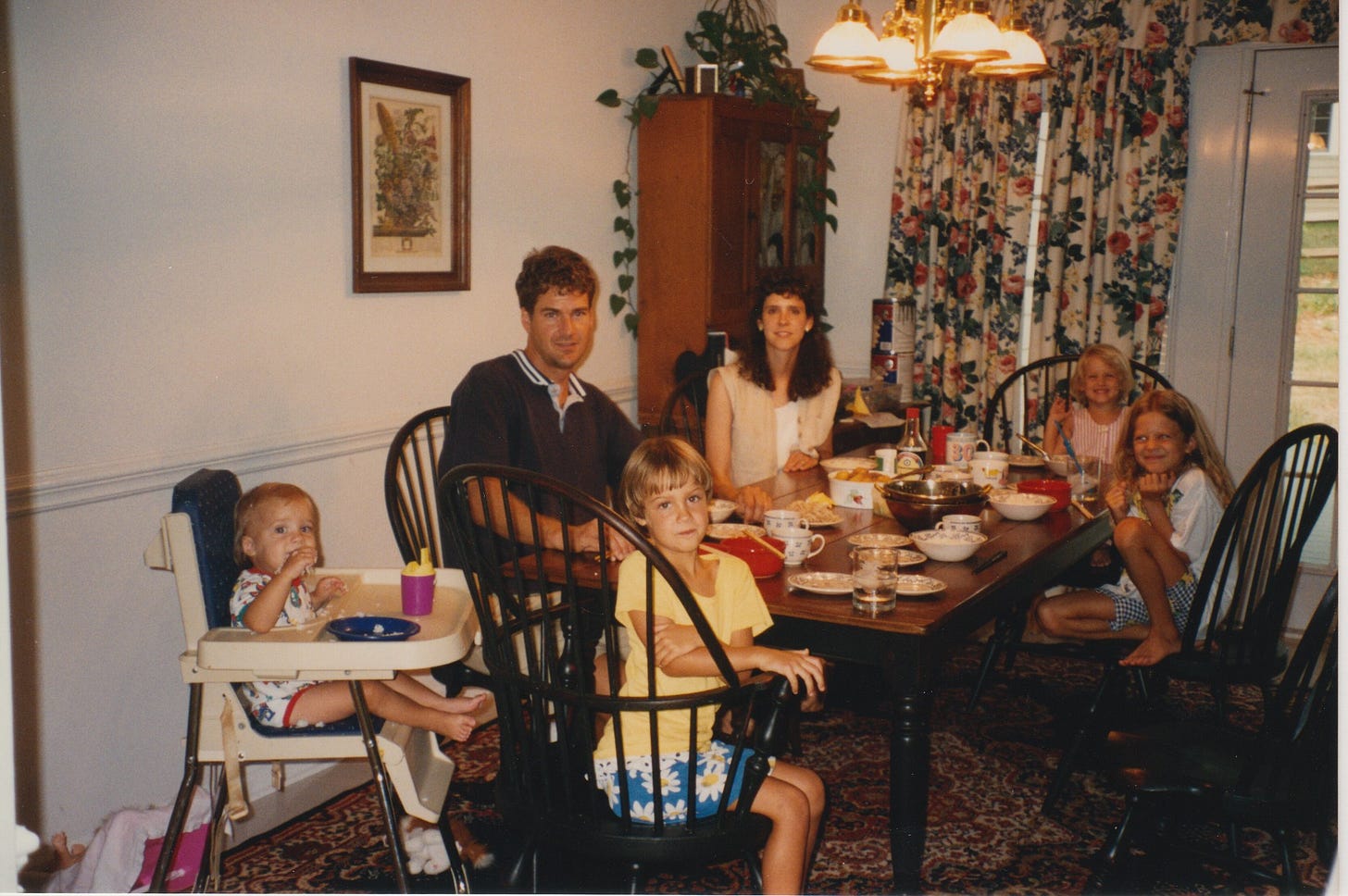

Reading these chapters made me think of the homes of my childhood, particularly my family’s home on Ash Cove Lane (below) and my grandparents’ home on Sapona Lane (also shown below).

I love this passage about how our childhood homes are inscribed in our bodies:

“But over and beyond our memories, the house we were born in is physically inscribed in us. It is a group of organic habits. After twenty years, in spite of all the other anonymous stairways, we would recapture the reflexes of the ‘first stairway,’ we would not stumble on that rather high step. The house’s entire being would open up, faithful to our own being. We would push the door that creaks with the same gesture, we would find our way in the dark to the distant attic. The feel of the tiniest latch has remained in our hands.”

I haven’t lived in that home since I was quite small, but I remember every room, every piece of furniture, every flaw, every work of art.

Memory champions, as shared in Moonwalking with Einstein, almost always use their childhood homes to remember hundreds of numbers in a sequence. Using your childhood home as your “memory palace” is an infallible choice, because you’ll never forget any bit of it. Your childhood home is always with you.

My grandparents’ gracious home, which backed up to Lake Tillery, is another one of those homes for me. Every corner and room of their house remains vivid in my imagination.

Although neither of these homes remain in possession of the family, they will always live on in my memory.

There is more to say on all this, I suspect, especially what Bachelard writes about the home coming alive through our care for it, but I will leave this here for now, as a reminder to myself. What kind of home do I want our boys to carry with them always? What will they remember in their dreams, thirty years from now? How can I shape our home to make their imaginations come alive?

Wow, thanks for this introduction to a book I clearly need to read!