I'm so glad I didn't go to grad school

When there's more than one way to maintain your feminist credentials

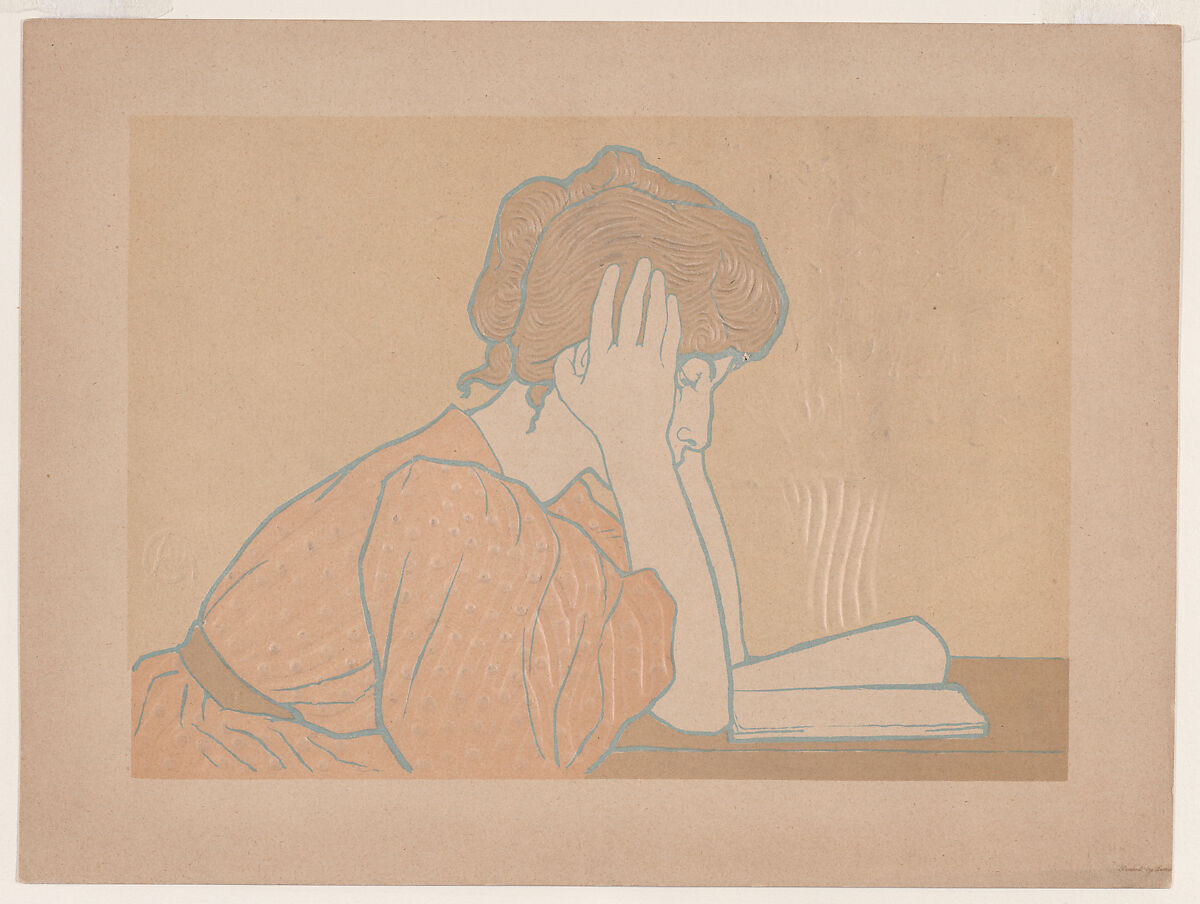

I was a run-of-the-mill undergrad English major and got very much into Virginia Woolf. It’s an unwritten requirement for girl English majors to have a Woolf phase, and mine probably lasted longer than most.

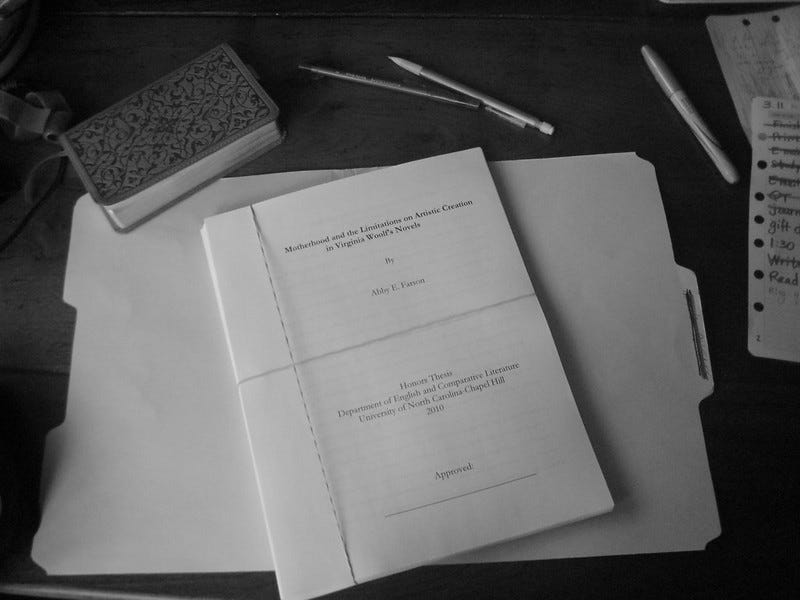

Loving books and talking about them, especially ones by sensitive, ill British women, I decided I’d get a Ph.D. in English after I graduated. I was double-majoring in journalism, and I wasn’t sure I could survive the cutthroat environment of the newsroom. I could much more envision myself holed up in a tiny office, surrounded by books, grading stacks of terrible papers, happy and isolated. To fulfill this grad school dream, I set about writing a laboriously self-important undergraduate thesis on Woolf’s portrayal of mothers as “alternative” artists, forced by their times to pursue unorthodox ways of expressing themselves creatively.

My thesis advisor was a no-nonsense Jewish lesbian, Dr. C., whom I never saw smile. She was hard on me, and I benefited from her withering critique of my 300-page thesis. Thanks to her encouragement and sharp editing, I graduated with honors and received a departmental award for my long, tedious paper. (I came in second place to a girl who… also wrote her thesis about Woolf.)

A few weeks before I turned in my final draft, I met with Dr. C. in her sunny office overlooking one of the campus quads. She wanted to talk about which grad schools I’d be applying to and which letters of recommendation she needed to get in order on my behalf.

I walked into her office that day with a lot of hesitation.

I hadn’t told her that I’d fallen in love and gotten engaged to this blue-eyed Christian boy that I’d met at an evening prayer service. He was applying to poetry MFA programs, and we’d decided that he would do grad school first, and then I’d go to school after he was finished. I was happy with the decision.

I was beginning to have the first inkling of doubt about the sustainability of a career in academia. Much of it appealed to me, but much of it—the bureaucracy, the never-ending cycles of school, the political jockeying for favor—did not. That year I worked as an intern for the university press and saw first-hand what an uphill slog it was to get published as a humanities professor. Getting married at 22 sounded far more appealing.

“I’ve been looking at a few schools,” I told her, “but I might wait a little before applying.”

“Why?” She looked at me over her glasses.

“Well, I didn’t mention this, but I… well, I’m getting married two weeks after graduation.”

She raised her eyebrows. She did not smile or congratulate me. She just stared at me and said, “Why on earth would you do that?”

I mumbled something about how great Guion was and how he was smart, he was a poet, too, and we really got on well. I promised that I’d go to grad school, too, as soon as he was finished. She listened to me with an unblinking look of disapproval. I was embarrassed; I wanted to say something that would make her proud of me, that would make her think I wasn’t betraying all of the feminist ideals we’d talked about for the better part of a year.

She looked at her lap and then said, “I’m sorry to hear that, Abby. You’ve worked so hard. You deserve to go to school and pursue your academic career.”

I protested that I would, that Guion wouldn’t ever keep me from my shimmering future as a lady English professor, but I could tell she didn’t buy a word of it.

I left her office feeling a weight of shame, something I hadn’t felt at all about my engagement before. Had I just turned in my feminist credentials? Was I now relegated to a life of domestic drudgery as a Christian housewife? Her disapproval nagged at me. I wanted to marry Guion as soon as possible, but I also wanted Dr. C. to be proud of me. I wondered if my pending marriage meant I was about to commit feminist suicide.

I of course never did go to grad school. After we married and moved for Guion to begin the MFA program at UVA, I took a job as a copy editor at a non-profit, editing an academic finance journal. I was content, toiling away in my cubicle and finding a useful outlet for my love of fixing other people’s messy sentences. We lived in a little apartment in a trendy neighborhood near downtown and had nothing to do but have sex, go to concerts, and make lots of interesting new friends.

Contrary to Dr. C.’s suspicions, marrying Guion never kept me from my supposed dreams of being an English professor. If anything, he wouldn’t let me give up on the notion. For years, he badgered me about applying, saying it was my time, cajoling me to investigate schools and finally send in some applications. He even bought me a GRE prep book one year as a birthday present. I looked at some of the algebra problems, shuddered, and never opened it again. I wasn’t motivated.

A Ph.D. in English seemed like a bad investment, after seeing so many friends frustrated by their lack of options after spending years and thousands of dollars to write a dissertation no one would read and then get relegated to teaching in a tiny, unpromising college in Oklahoma. I would continue to read ravenously on my own and enjoy being a simple copy editor, poring over the Chicago Manual of Style and improving the prose of humorless business professors.

I know Dr. C. would be thoroughly unconvinced, if she were to hear me now, but I am deeply content. I would like to tell her that I do not regret passing up a Ph.D. in English for even a moment. My life is full, fuller than I think it might have been on this prior trajectory.

I wonder from time to time, what it might have been like, but I don’t like the vision of myself that I see. Becoming an academic would have ossified some of my worst qualities (pretentiousness, exclusivity, narrow-mindedness, intellectual rigidity, to name a few). In my social circle, I remain one of the least-educated people, and I have found comfort in that status, a status that would have horrified junior-year Abby. I feel freer than I might have otherwise been, at least in the life of the mind.

Currently Reading

The Book of Disquiet, Fernando Pessoa

Directions to Myself, Heidi Julavits

Jake and I were just talking about something along these same lines this last night. He just graduated from Georgetown (he went on the GI bill) so I've interfaced with a lot of really high achieving individuals and it becomes a little bit of a competition between people-what schools you went to, what jobs you did, what you want to do with your career, etc. etc. Inevitably someone will ask me, "Where do you work?" I smile as kindly as I can and say, "I work at the Minute Clinic, I don't take work home with me and I have time to do other things I love." It's interesting because sometimes I see people visibly relax and then they start talking about things they enjoy outside of their profession, because I removed myself from the competition by defaulting letting them win.

It makes me also think of the Marion Woodman in Addiction to Perfection, “Living by principles is not living your own life. It is easier to try and be better than you are than to be who you are. If you are trying to live by ideals, you are constantly plagued by a sense of unreality. Somewhere you think there must be some joy; it can’t be all “must,” “ought to,” “have to,” And when the crunch comes, you have to recognize the truth: you weren’t there.”

So this is a long winded way of saying, I admire you now and your younger 22 year old self for having the courage to do what you wanted to do with your life instead of allowing your whole life to be shaped by anyone else's idea of what that should look for your life should look like.