What’s the point of reading anymore?

Read so you can have great TASTE

You know that feeling when you see yourself in an icky character? A character who makes your skin crawl precisely because they’re so much like you?

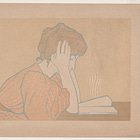

I keep getting this clammy feeling when I encounter Frederica Potter, the vain, pedantic heroine of A.S. Byatt’s tetralogy. Specifically, Frederica is so oriented toward text that she lets it blot out the whole world. I can’t find the exact passage, but somewhere in Still Life, it’s said that Frederica had to be taught to find beauty in visual things, so overwhelming was her preference for words over images.

I feel regrettably like her. Having worked now for nine years at a graphic design company, I have had to be taught how to see, how to perceive balance in grid layouts and discern proper typesetting on the web. Left to my own devices, I’m too focused on the words themselves and what they mean. I was once (fittingly) kicked out of graphic design critique for asking too many questions about the text itself instead of about the art direction.

In The Virgin in the Garden, this fixation of Frederica’s is described thusly:

“Frederica read, twice, the information on this poster, vanished days and hours at the Arts Theatre in 1950. Then she read the titles of the books on the shelves nearest her. She was magnetised by print, by lettering, she took sensual pleasure in reading anything at all, instructions about Harpic and fire alarms, lists, or, as now, the titles of books. Notes Towards a Definition of Culture. A la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Théâtre Complet de Racine.”

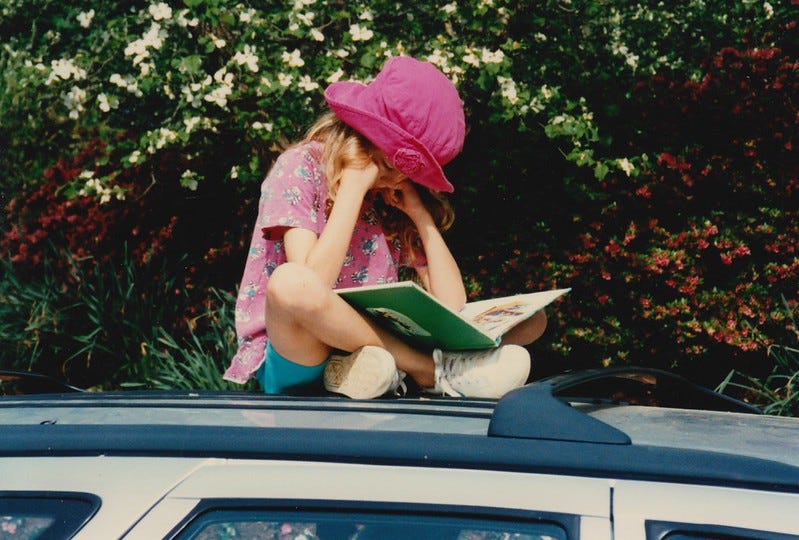

She took sensual pleasure in reading anything at all. What a strange way to be in the world. And yet I feel like I was born this way. One of my earliest memories, around the age of three, involves sitting on my grandfather’s lap while he had his morning coffee with his newspaper. Peering up at those great sheets of paper, I’d call out all the letters I recognized, in every column, doggedly trying to figure out what they were trying to tell me.

At a moment when we are suffused with text and yet deep reading suffers, how does an obsession with words shape taste? Does reading change what we want? And does it even matter?

The death of reading

Because reading is my way of making sense of the world, I shiver with dread when I encounter such reports on the state of reading and literacy, at home and abroad. Consider, if you will:

Only 16% of Americans read for pleasure anymore, which represents a 40% drop over the past two decades.1

Literacy in most developed countries is declining or stagnating, something we’d once only seen in times of war or extreme crisis.2

Accordingly, the dramatic decline in reading is correlated with a decline in various measures of cognitive ability.3

Most college students can’t understand the first paragraph of Bleak House, a book that young children once read and easily comprehended. They can’t handle reading long novels week to week, much less understand or follow them. And these are the English majors. One literature professor described his students simply as being “functionally illiterate.”4

And so on. The source of this decline is obvious (phones) and almost not worth mentioning or lamenting. Instead, I’m curious about the question, “So what?”

What does it matter if no one reads anymore? And how will that affect what we call culture? How will the death of reading change what we find to be beautiful, virtuous, and true?

What’s the point of books—reading them ourselves; writing them, even—if we can reach into the vast bag of words proffered by large language models to find an “answer” to every conceivable human question?

I’ve come to believe that reading books forms our taste, which will be an increasingly rare and uniquely human capability in the murky years ahead.

From whence does taste come?

Webster’s 1913 dictionary, to which I often retreat, includes the following as its fifth definition of taste:

5. The power of perceiving and relishing excellence in human performances; the faculty of discerning beauty, order, congruity, proportion, symmetry, or whatever constitutes excellence, particularly in the fine arts and belles-letters; critical judgment; discernment.

A woman with great taste has developed, through careful study and observation, the ability to detect what is beautiful and what is not, what is ordered and what is not, what is excellent and what is not. In other words, she is discerning.

So often we make “taste” a synonym for elitism, snobbishness, outlandish materialism, but in its origins, it has nothing to do with money. Anyone can have taste. It’s there for the taking. But it requires something from us: ongoing diligence and discipline to sharpen our powers of perception.

If TikTok’s algorithms are the arbiter of taste, if they determine what we find good or true or beautiful, the lowest common denominator, primed to our superficially personal “interests,” will rule the day. The populist paranoias, the hyperbolic hand-wringing, the pornification of human relationships will dominate (as they already do). We’re getting measurably dumber.5 And on top of that, we have deplorable taste.

Our taste is terrible because we’ve lost the ability to be discerning.

Life online has so addled our brains, so blinded us with the shiny and the false, that we can no longer tell what is good, true, and beautiful. I wager that the death of reading is connected to this death of taste. When everything we ingest is mediated through screens, we lose the capacity for critical thinking, reflection, and reason that reading demands.6

Reading is dying out. Books might exist today to feed the gaping maw of ChatGPT. But they might have been (and could still be!) our best guidebooks to taste. More than television. More than theater. More than advertising. More than spectacle. Great taste might have been offered up to us via the written word.

It’s not about intelligence. It’s about discernment.

Computers are smarter than we are. They can access all written human knowledge in mere seconds, synthesize it, solve infinite math problems, sequence DNA, operate weapons: You name it, a computer can perform a knowledge-based task better than you (and me).

From staunch non-readers, I’ve heard this truism used as a defense for why we don’t need to read anymore. Books are done; they had their day in the sun! Now we don’t need to know or remember anything. What’s the point of reading, if everything we could possibly read about or know could be regurgitated to us in a second by a bot?

But for those of us who still read for pleasure, that 16% remnant, we don’t read in the hopes that we can keep up with computers or emerging tech. We don’t read to maintain our “book smarts.” We don’t read to keep up literacy rates to fight the rising tide of machines.

We read because of what happens to us, to our very spirits, when we do: to parse text, to turn off a screen, to meditate on meaning, to form arguments, to return to something good, beautiful, and true that has been written down by someone wiser than ourselves.

This is what deep reading can still offer us. Because the other thread of that hundred-year-old Webster’s definition that I love is the use of that word relishing. (To taste with pleasure! To lick!)

Having great taste doesn’t mean just having great powers of perception: It also means to experience joy and find delight in the beautifully made thing.

What’s your mind for? Why cultivate your desires at all? Why feed the spirit something nourishing instead of something depleting?

No matter what the computer overlords take from us, I believe that we are called into an intimate relationship with beauty and goodness. Human beings have a radical capacity to recognize and name things as such. We lose a great deal of our humanity, our civilizational energies, even, if we lose our taste. Reading—and relishing—books remains our best avenue to improve our twin capacities for discernment and enjoyment.

Related screeds

Also:

Possible future thread: In terms of which forms or media shape our taste, is my bias for text over images warranted? Come at me, graphic designers…

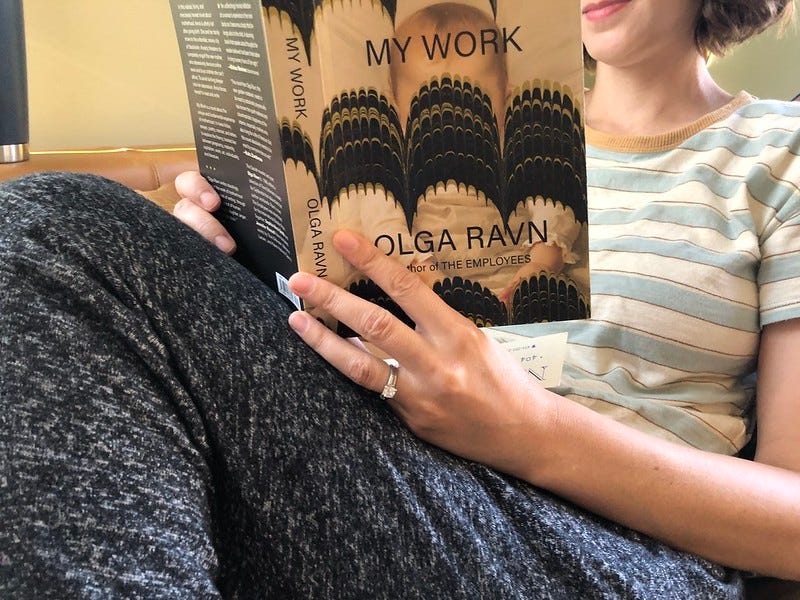

Currently reading

Absence of Mind, Marilynne Robinson

How to End a Story, Helen Garner

The Millstone, Margaret Drabble

“Reading for Pleasure Has Declined by a ‘Deeply Concerning’ 40 Percent Over the Past Two Decades,” Smithsonian Magazine (26 August 2025).

OECD press release (10 December 2024).

As writer James Marriott says, “Regular reading is associated with a number of cognitive benefits, benefits including improved memory and attention span, better analytical thinking, improved verbal fluency, and lower rates of cognitive decline in later life.” From “The Dawn of the Post-Literate Society,” James Marriott (19 September 2025).

“The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” The Atlantic (1 October 2024).

“In the absence of editorial controls on quality—of either the centralized variety of old or the decentralized variety imagined by Benkler—the information about the world that spreads through online cascades skews toward the biased, the exaggerated, and the fake. Real facts tend to be mundane and drab. Leaving the emotions uncharged, they stream by without making much of an impression on the nervous system. Falsehoods are constructed to be novel and surprising, exciting and infuriating. They grab attention. They get shared. When human beings serve as the repeaters in a communication network—when they take on a signal-amplification role while still acting in their traditional roles as creators and interpreters of messages—Shannon’s distinction between mechanism and meaning gets shakier still. Meaning becomes a network effect. What’s true is what comes out of the machine most often.” — Superbloom, Nicholas Carr

Wonderful interrogation of the value of taste and beauty being all about capital-D discernment. It's a capacity we all have too! Please check out The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty and Other Matters by the late great MacArthur Genius art critic Dave Hickey. It's the apex exposition of what AFP is getting into here