When I think of the internet, especially now that it’s run by janky AI, I think of an overflowing sewer I once saw in New York City. A constant stream of hot slop. I don’t have to describe it with any more detail than that. You get the picture.

Online, we wade daily in this stream of slop. And the lowest common denominator floats to the surface: The vulgar entertainment and entertainers. The crass marketers. The platforms and apps and products that will happily take our money in exchange for our souls.

Not news, I know, but I’ve been fixated on a byproduct of living in the slop of monoculture.

It’s this: Monocultural slop makes us suspicious of great art.

We’ve become so inured to the braindead megaphone, to reality TV and TikTok and Taylor Swift being the height of culture, that when someone dares to say something positive about Dostoyevsky or Degas, eyes roll. The label of pretentious is immediately proffered. Only snobs say they like reading Proust or going to art museums! They say it to sound fancy.

That could be true for some, that it’s just for cache and status, but I don’t believe that loving great art is only for the elite. It’s for everyone. It just takes more effort.

This passage from writer Henry Begler expresses the sentiment so well:

“It does take more work to like paintings than a pop song. It’s a process of learning to tune one’s awareness, of entering into a relationship both passive (open and receptive) and active (once received, processing and perhaps arguing) with the painting, of learning to really focus on one image in an age of extreme image saturation.

But this is what the vulgar form of poptimism misses and [art critic Peter] Schjeldahl knew: anyone can do it. Anyone can learn to cook if they put in the time, anyone can get strong if they go to the gym. I didn’t used to think much of paintings and I would go to art museums and leave bored and slightly confused. When I read Schjeldahl and Robert Hughes and John Berger and TJ Clark I was slowly taught this process of emotional reception and one day I went to a museum and I found that my entire way of perceiving paintings had changed and they all buzzed with life around me. It was like I could suddenly sit down at a piano and play a concerto. And you can teach yourself to like opera or read Joyce or any other snooty-coded thing if you put in a little time and effort. You might not have that much of a response to it, but you can understand it. Take notes, it helps. And go alone.”

Take notes, it helps!

I felt this truth so much in Vienna.

Our guide, Tate, encouraged us to take notes by hand, all day, wherever we went. In this way, we began to think critically about what we were seeing and experiencing and pondering. In this way, we began to heighten our sensitivity. No, I didn’t have a life-changing experience at the Wagner opera; I didn’t walk away with a deep love of the art form; but I am sure that, with time, exposure, and openness, I could learn to love and appreciate it. I loved hearing from other people who loved it, other people who could see and hear what I could not.

It is all there for the taking.

There is depth and richness and insight, laid out in front of us. There is a reason why we have returned to certain artists, over and over again, for centuries. And it’s not because we are all snobs. It’s because these artists have unlocked something about humanity, the universe, and the divine that others have not.

It is good to do hard things. It is OK if loving great art takes effort. It does not have to go down easy to be good or worthwhile. (Slop goes down easy.)

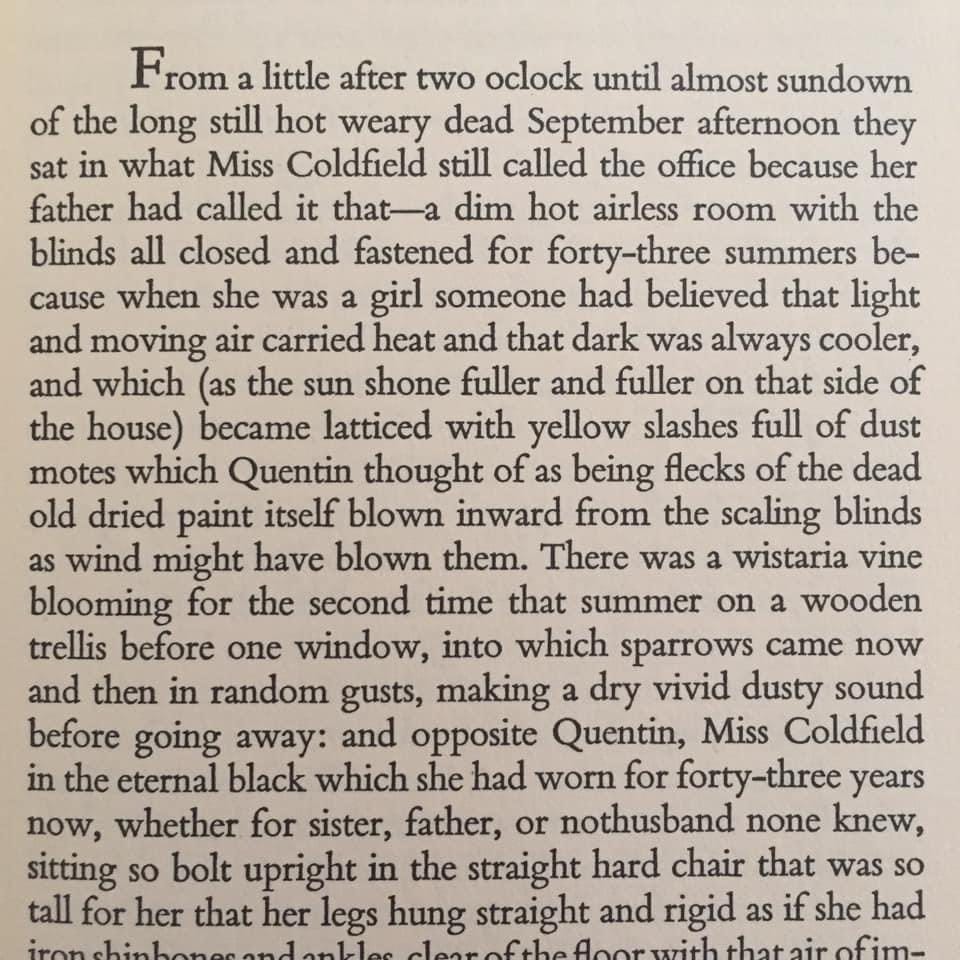

I’ll always remember attempting Absalom, Absalom! for the first time, when I was probably about 20 years old. It felt so intimidating to me. I could barely get past the first page, but I knew it was supposed to be good.

I wanted to know why. I got a notebook and started writing about what confused me or what seemed connected while I read. I filled that notebook with questions and my paperback copy with marginalia. And it was one of the most moving reading experiences of my life. Still, to this day, I can’t tell you much about the plot, but I can remember the exquisite feeling of mind-opening depth and curiosity from encountering that difficult novel. I’ll always remember it. It’ll always be an important part of my reading life.

Novelist Celine Nguyen writes in her newsletter that she was a victim of the “vulgar poptimism” that Begler describes: the prevalent belief that “everything is just as good as everything else and no one actually likes anything challenging—they’re lying to themselves, or to you.”

This was why I clung onto pop culture for so long—because I thought that the “challenging” books (and films, and music, and performances) were less enjoyable. Reading Proust showed me that this was false. The supposedly impenetrable, inscrutable, overtly intellectual works—they were better, not because they offered more cultural capital and clout, but because they made me feel alive.

It’s not about status or wealth. It’s not about snobbery. (Some of the poorest people I know are the most cultured people I know. Some of the richest people I know are the least cultured people I know.)

It’s about this short life that we have been given! It’s about tuning our awareness. It’s about being open to beauty and wisdom—and to being challenged and changed by it.

Everything is not just as good as everything else.

Beauty and wisdom do not flow out of our precious devices, which have made life so, so easy. We have become soft and slow. We have become dulled to effort. It is much easier to skate on the surface of things. I too am quickly worn down, when bedtime goes awry and when a fresh new illness has approached the household and when the floor desperately needs to be mopped, but, oh, life is much too short for slop.

Related

Currently reading

The World According to Garp, John Irving

I Who Have Never Known Men, Jacqueline Harpman

Ways of Seeing, John Berger