Wisdom shall not come from the internet

We need to breathe on people and hold books in our hands

No truth on a screen

Here’s a story about me not taking my own advice.

Recently, I fell into a common trap of the screen-mediated life, looking for wisdom that was not there. I created a real panic spiral that was absolutely unnecessary.

Based on a brief suggestion from a telehealth pediatrician, I went down a dark path of panic-Googling, late into the night, getting volumes of AI-generated (and often conflicting) health advice, and ended up convincing myself that our middle child had a serious chronic illness.

The next morning, having slept only a few hours due to this surging anxiety, I took him in to see a real flesh-and-blood pediatrician. I was barely able to take a deep breath for 24 hours for fear. My face was bloodless, drawn. I kept imagining what the rest of our life, what the rest of his tender young life, would be like, now that the screens had convinced me of this grim fate.

But when the physician walked in the room and looked at me and Felix and smiled, I felt the entire register of my body shift. I felt a physical letdown in my gut; it was wild. “He’s fine,” she said. (And he was, and is.) All of the panic was for nothing. My panic was engineered by letting screens and robots mediate my real life.

This is one example, but it’s indicative of where we so often find ourselves in 2025.

We can’t trust most of what comes to us on screens anymore.

In an era of deep fakes and hallucinating AI, there’s increasingly less and less that we can trust online.

Is that a real quotation? Is that a real news story? Is that even a real person chatting with me? Most of the time, it’s not. We’re swimming in a daily flood of misinformation.

Fake news spreads faster than true. Lies are 70% more likely to be retweeted than truths, and we’re so enchanted by it and so enamored with the outrage and entertainment that we don’t care about veracity anymore.1

In his latest book Superbloom, Nicholas Carr writes about how repetition is the law of internet discourse.

Saying something over and over again makes us (and the algorithms) believe that it’s true. So when we see those thousands of retweeted lies, we start to accept them. We think: Well, it must be true if 12K people liked this, and we hit the repost button, because that headline is truly shocking; people ought to know.

Carr says (emphasis added):

“If social media has an intellectual creed, it is a creed of repetition—the creed of the mob, the huckster, and the tyrant. ‘Endless repetition,’ Victor Klemperer observed of the Nazis as they took power in 1933, ‘appears to be one of the stylistic features of their language.’ The unending competition to produce messages that will get repeated, that will propagate through the network, is a battle for meaning as well as influence. In the absence of editorial controls on quality—of either the centralized variety of old or the decentralized variety imagined by Benkler—the information about the world that spreads through online cascades skews toward the biased, the exaggerated, and the fake.”

The biased, the exaggerated, and the fake: This is most of what we’re consuming when we’re on our phones. Sit with that for a minute, if you will. It makes me shudder when I think of my own browsing behavior.

And so. Two predictable takes:

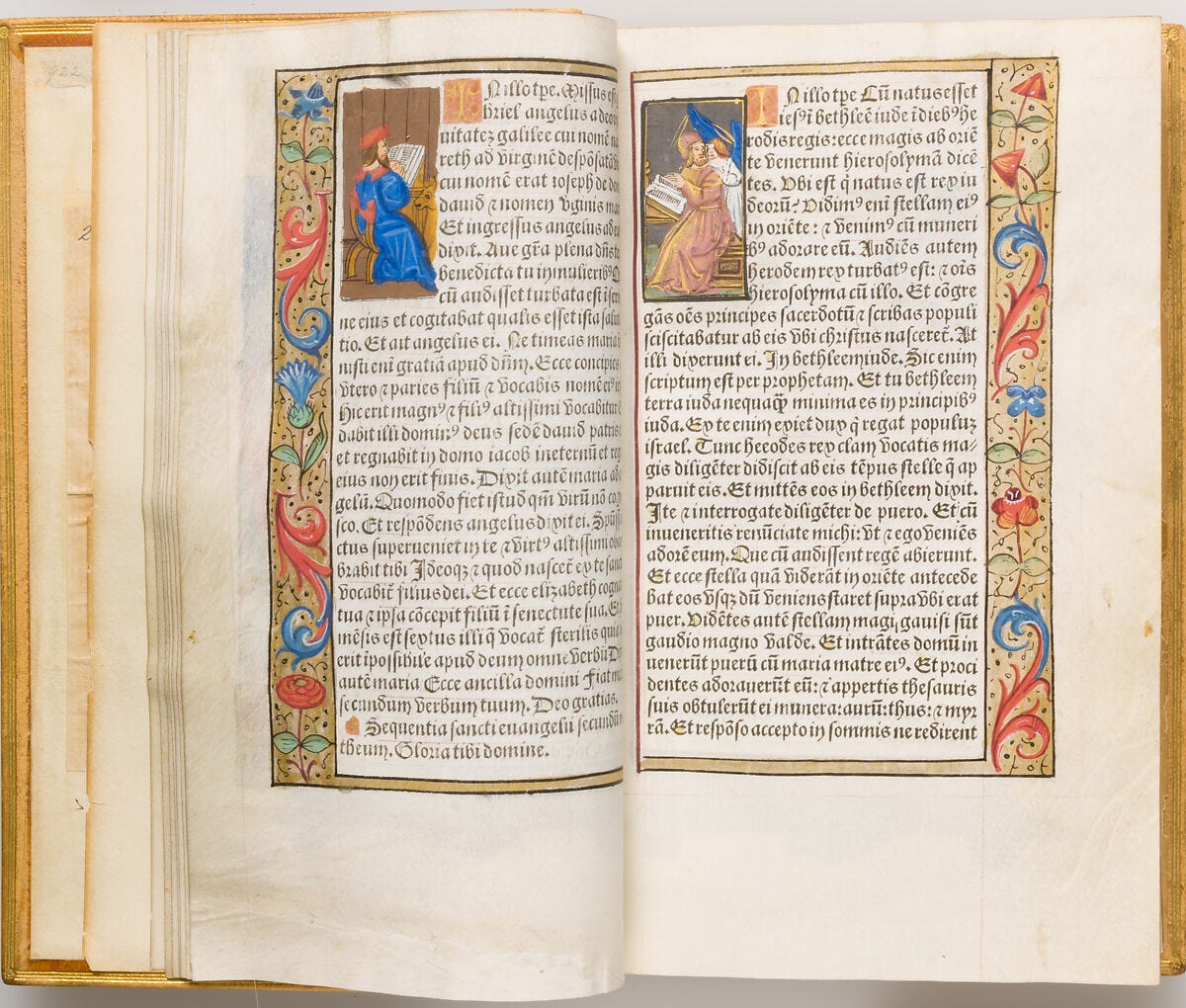

Reading books matters more than ever

As I trust less and less of the internet, books have increased in value.

They’ve always been incredibly valuable to me, since I was small, but that line from Carr has stuck with me: In the absence of editorial controls on quality…

The internet has no censor, no quality control. What’s biased, exaggerated, and fake will always win the day. As our online life is spiraling out of control and further into unreality, books remain steady, durable, and trustworthy.

And it’s mostly because books are slow.

They take a long time to write. They take a long time to get published. They take a long time to read.

Truth should come to us slowly. We should evaluate it from a variety of perspectives. We should roll it around in our mind. We should sit with it. We should labor over how to comprehend and apply it. We should look up conflicting reports. We should talk about it over a glass of wine with companions. We should keep asking questions.

For the past handful of centuries, we haven’t improved upon the technology of the book for the dissemination of knowledge.

When held up against how the internet is trending, I crave a printed page. I feel the virtue of its slowness, spending so much time online, as I do.

The difficulty and tediousness of books still calls to me—and calls to me with even greater appeal given what the internet is like.

I hope that it is precisely the difficulty, tediousness, and slowness of books that will preserve them as valuable. We can fight back against the biased, the exaggerated, and the fake. In this losing battle in the information war, books may still be our best tactic and hope.

Being with people matters more than ever

As with books, I am also moved by the difficulty and tediousness of people.

Like many bookish people, I cherish my identity as an “introvert.”

If given the choice between a large party and a night at home with a stack of novels, I’ll always pick the novels.

But I’m increasingly beginning to feel like this is often the wrong choice. I grow antsy and dull if I keep too much to myself. Even a bad party is better than no party at all.

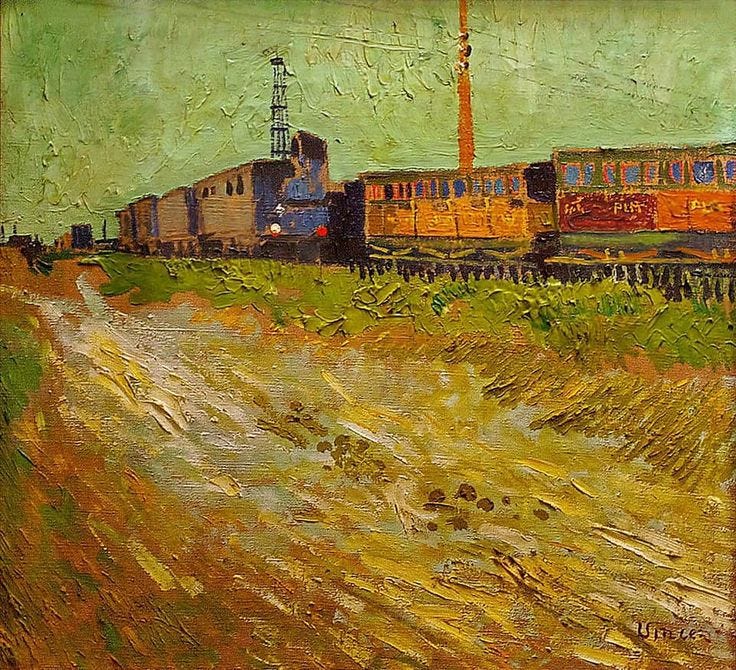

In a brilliant, arresting essay by Derek Thompson in the Atlantic (read sans paywall), he shares the outcome of a study on a train:

Several years ago, Nick Epley, a psychologist at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, asked commuter-train passengers to make a prediction: How would they feel if asked to spend the ride talking with a stranger? Most participants predicted that quiet solitude would make for a better commute than having a long chat with someone they didn’t know. Then Epley’s team created an experiment in which some people were asked to keep to themselves, while others were instructed to talk with a stranger (“The longer the conversation, the better,” participants were told). Afterward, people filled out a questionnaire. How did they feel? Despite the broad assumption that the best commute is a silent one, the people instructed to talk with strangers actually reported feeling significantly more positive than those who’d kept to themselves. “A fundamental paradox at the core of human life is that we are highly social and made better in every way by being around people,” Epley said. “And yet over and over, we have opportunities to connect that we don’t take, or even actively reject, and it is a terrible mistake.”

We are made better in every way by being around people. And it’s people in the flesh: with bodies! It’s not people mediated through a screen. Thompson goes on:

Our “mistaken” preference for solitude could emerge from a misplaced anxiety that other people aren’t that interested in talking with us, or that they would find our company bothersome. “But in reality,” Epley told me, “social interaction is not very uncertain, because of the principle of reciprocity. If you say hello to someone, they’ll typically say hello back to you. If you give somebody a compliment, they’ll typically say thank you.” Many people, it seems, are not social enough for their own good. They too often seek comfort in solitude, when they would actually find joy in connection.

Despite a consumer economy that seems optimized for introverted behavior, we would have happier days, years, and lives if we resisted the undertow of the convenience curse—if we talked with more strangers, belonged to more groups, and left the house for more activities.

Choose people, choose connection. Be aware of the danger of staying too much at home, comfortable though it may be. Resist the machine-mediated life. In this way, we might avoid panic spirals and gain wisdom.

Related

Why AI Can Never Be Hospitable, a great take by my wonderful colleague Jen Eberline; so proud to publish this yesterday

The Relationship Is the Job, on what remains when we automate most manual and cognitive labor

Why We Work Together, another great take by another wonderful colleague, Zack Bryant

“Patience with others is Love, Patience with self is Hope, Patience with God is Faith.”

— Egyptian theologian Adel Bestavros, quoted in David Zahl’s excellent new book The Big Relief

Currently reading

The Topeka School, Ben Lerner

Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage, Alice Munro

Caste, Isabel Wilkerson

This is fantastic!