A few years ago, I was walking with two colleagues, and they were talking about how great it was that the man’s wife stayed at home with their children.

The woman walking with us mentioned how her mother worked long hours throughout her childhood and how neglected she felt because of it. “It’s always better for the mom to be home with the kids,” he said.

They had apparently forgotten that I was there, because I was that disappointing mother—as they well knew—who worked full time outside of the home. I was not, clearly, “home with the kids.”

The brief conversation stuck with me like a thorn. Or, more accurately, it felt like an old wound that had been reopened.

Their discussion reinforced a message I’ve heard my whole life: There’s a right way to be a mother. And there’s a wrong way. And working outside the home is the wrong way.

I recently finished the very dark Danish postpartum novel My Work, by Olga Ravn. Reflecting on her new state as a mother, the narrator observes:

“She regards woman as an antiquated form. She thinks motherhood is designed for a woman who no longer exists. A woman who is entirely dedicated to her child, her house, who stays at home while her husband goes to work. But even though she can see that the form is false, this idea of the mother is lodged so deep inside her it can’t be extricated, so she’s left hating herself for not spending her life staring deep into her child’s blue eyes while drying off a billion plates with a dish towel.”

A billion plates! I too feel “this idea of the mother is lodged so deep inside” me that I cannot reconcile it with what I have chosen to do instead. It’s the narrator’s question of the design of motherhood being at odds with the modern woman that also sticks with me.

Have we redesigned modern life and mothering so much that it no longer accords with what women are for and meant to do?

Am I supposed to be at home, drying off a billion plates? Then why does that prospect feel so soul-crushing to me? Even as I dearly love my little children and staring into their blue eyes?

I spent 10 years waffling over whether I wanted kids because I knew I didn’t want to be a stay-at-home mom.

I’d been told my whole life that if I was going to have kids, then I’d better stay at home with them. That was the only way.

This was modeled for me and implicitly and explicitly expressed throughout my childhood and young adulthood. Moms stay home. Dads work. Moms can go to college, sure, but once they fall pregnant, that’s it for the public world.

I grew up in a community, as you may suspect, where every woman was a stay-at-home mom, but she was working, too, because she was teaching her kids full time. My mom was an even more ambitious case, because not only was she a mom at home, a mom homeschooling four children, but she owned a business with her sister—a successful retail shop in uptown Charlotte, for more than three decades. She was, to put it mildly, working.

Even still, she expressed that she couldn’t understand why women would have children if they were just going to pay someone else to watch them.

I heard this and felt regret. I felt resignation, too, and assumed that I’d just never have kids. Because I knew, from a young age, that I didn’t want to be home all the time. I wanted to be in the world. I wanted to work and exchange ideas and compete. I didn’t want to be told that because I was a woman, I only had one vocational option, and that was being home.

I love my kids, and I love the work that I do. Loving my children and my job in tandem requires sacrifices.

It seems to me that these sacrifices often make mothers more uncomfortable than fathers.

I had a wonderful childhood. My mother is responsible for a large part of that, spending every moment of every day with us for the vast majority of our young lives.

Will my children have a subpar childhood because I didn’t do the same? Will they say, as my colleague did, that they felt neglected because their mother worked? Will they describe me as a bad mother?

These questions haunt and nag me. I am rankled that children seem to rarely feel angry about their fathers working. I felt neglected because my Dad had a job! He had the gall to work outside the home! Even young children seem to know that dads are supposed to work. Moms are supposed to be home.

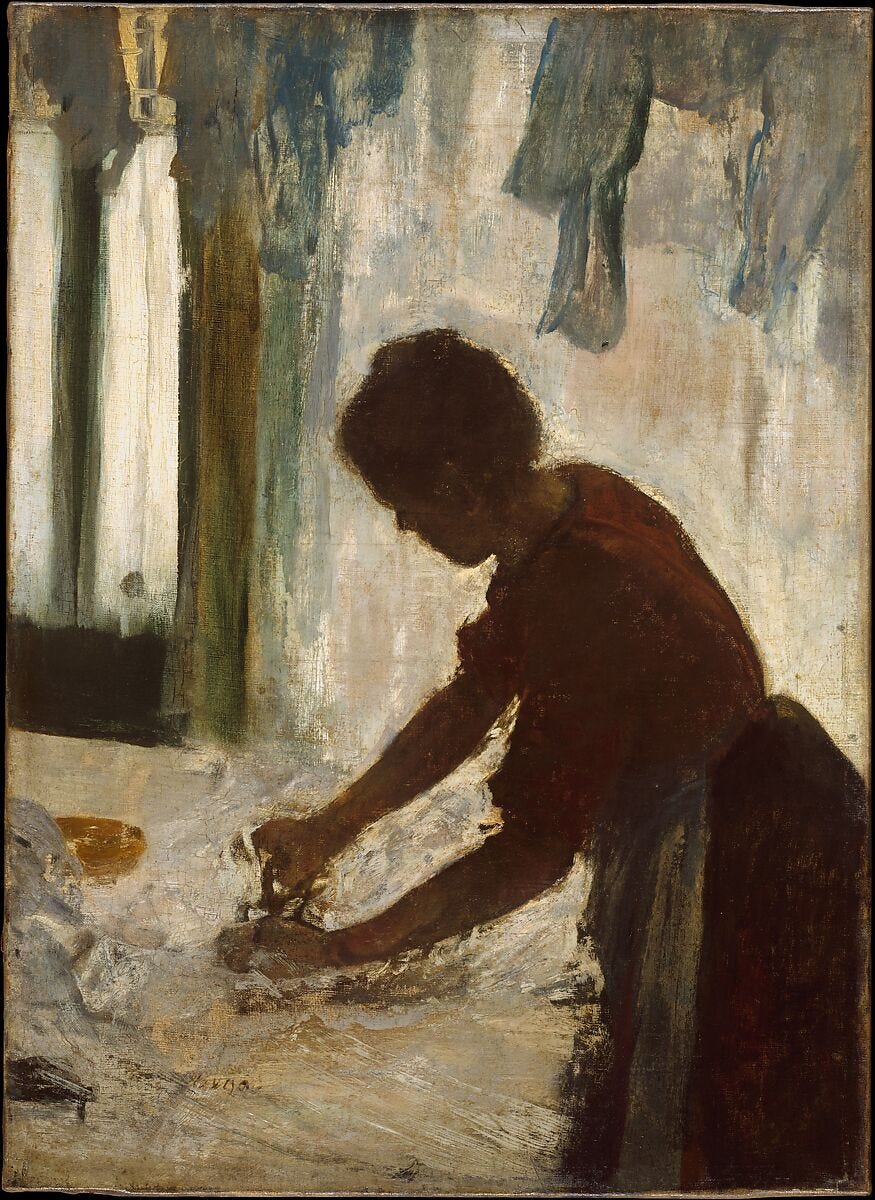

Women have always worked. And most women have worked “outside the home,” even if it was adjacent to home. They were in the woods, foraging, or on the farm, harvesting, or near the hearth, spinning and mending and cooking and tending, or at the market, selling or shopping.

Because women have always worked, women have also always needed a lot of help to raise their children, especially from other women.

In hunter-gatherer societies, alloparents (other caregivers) provide almost half of a child’s care. A study of hunter-gatherer communities in the DRC showed that by 18 months of age, the average child was being watched by 14 different community members a day.1 14 people a day! In another hunter-gatherer society, the Agta in the Philippines, researchers found that alloparents provided nearly three-quarters of the care for babies under age 2, and nearly 80% of care for children ages 2 to 6.2

As a mother who relies on other women3 to watch my children five days a week, I take some comfort in these findings. It’s actually not “unnatural” to have other people caring for your children. What’s unnatural, perhaps, is having to pay them to do it, and the loss of community, mutuality, shared help, which I acknowledge and grieve.

Based on how humans were made, I think we’re pushing two unnatural mothering extremes in the United States. The working mother is unnatural, and the stay-at-home mother is also unnatural.

The working mother has to labor long hours, pay incredible amounts of money for unstable childcare to low-income women who are still somehow underpaid, run her household like a business, still do the lion’s share of the domestic labor, and feel strapped for time and stressed to meet everyone’s emotional and domestic needs.

The at-home mother is isolated in her solitary dwelling, spending all day with her children and receiving no help, often spending long days feeling incredibly lonely, stifled, worn out, and desperate for some kind of a break and some sliver of life away from her children.

Neither extreme seems normal and healthy to me. But what are we to do? The working mom model is becoming more and more common. In 2023, 73% of mothers with children under 18 work outside of the home. And in 40% of families, the mothers are the breadwinner or sole earner (up from 11% in 1960). Increasingly, to stay at home and still make ends meet is regarded as a privilege.

Flexibility for working parents, regardless of sex, is essential. I am grateful to work at a place that grants me a lot of leeway to care for my children when needed, to pick them up at school, to go to their luncheons, to be home with them when they’re sick. This is also a privilege in the U.S., one that is not afforded to every working mother, most of whom feel strapped and unable to care for their children and their home in the way that they would like.

I dream of a society that lightens the load on mothers. I’m not sure if this utopia has ever existed. Woman’s work is never done. But she has traditionally had a lot of help. Increasingly, I daydream about our long-standing joke of starting a “commune” with our closest friends and their families. But we probably won’t. We’ll keep slogging it out in the marketplace and finding ways to carve out more flexibility and freedom.

What does all of this mean for children? Specifically, will my children suffer for having had paid alloparents? Will they remember me as cold and unfeeling for having worked?

It’s a truism that no matter what choice a woman makes, whether she works outside the home or whether she doesn’t, she will be judged. She will feel some level of society’s censure. Mothers feel this in a way that fathers do not. Making peace with that relentless criticism, whether it’s external or whether it’s coming from within, is just another part of woman’s work.

I continue working and love working. I continue mothering and love mothering. I take a deep breath and try to filter the criticism, the absolute statements of right and wrong, with a measure of calm.

Care for your children. Love them and raise them up well, to have integrity and resilience and compassion. Do this whether your work is paid or whether your work is unpaid. Ask for lots of help. Create a community in which asking for and giving help is a central part of the economy. Identify and prioritize flourishing. Know when to hold fast and when to yield.

Currently reading

Trust, Hernan Diaz

Albion’s Seed, David Hackett Fischer

BoyMom, Ruth Whippman

https://www.cnn.com/2023/11/17/health/parenting-childcare-hunter-gatherers-wellness-scn/index.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/12/01/1216043849/bringing-up-a-baby-can-be-a-tough-and-lonely-job-heres-a-solution-alloparents

98% of the caregivers my children have had have been women, but the boys did finally get their first male teacher this year, which makes me so happy. I’m so thankful they have a male influence in their preschool and kindergarten years.