AI kills thought, humanity?

Composing with AI is like talking with someone who constantly interrupts you.

AI-generated writing suggestions and prompts are everywhere now. They’re in my inbox. They’re on my Google docs. They’re in my texts. They’re omnipresent. If I’m typing anything, AI is there, hovering over my shoulder, whispering a constant stream of mostly unhelpful suggestions.

How I hate trying to write with AI! It’s deadening. It cuts off the brain stem at the root.

I almost never take the robot’s suggestions. It’s rarely what I want. Instead, I feel frustrated and stymied and misunderstood.

This is the promise of artificial intelligence: to optimize everything—and to dehumanize us in the process. We don’t want to set limits on its uses. But there are very clear lanes, in my mind, where AI can and should be used—and where it should be banished.

In the creative, productive writing process, AI should have no place. Humans are messy and inconsistent and paradoxical. The machines can smooth all of that out. The machines can always write a correct sentence. The machines can be dull and perfect. I want none of that when I’m writing. The most interesting writing happens when a person—a human mind!—connects something unexpected.

In the creative process, it is stifling to have a robot whispering over your shoulder.

But the whispering robot is useful in other contexts. For example, this week, my primary care physician told me she was recording our conversation so that her AI tool could transcribe and categorize notes for her after our visit. She spent more time actively listening to me and looking at my face (rather than at her laptop) during the appointment because of this tool.

AI, in this instance, gave her back more of her humanity and elevated our interaction. This is a great use of the tool; I have no objections. Let the robots do what robots are good at—note-taking—and let the doctor be a human doctor with another human in the room.

I’m still unconvinced that generative writing—writing to find out what we think, writing to make sense of the world—will be a humanizing use of AI.

The large language models are getting better every minute, and they’re already more than capable of producing text that can mimic writers, even good ones. I don’t love that, but what I’m specifically irked by is the attempt by the machines to offload labor I want to do. I want to think for myself. I want to get better at writing. I don’t want the LLM to do any of that on my behalf.

Practically, I am trying to turn off these AI gremlins wherever I can. It gets harder with every passing day.

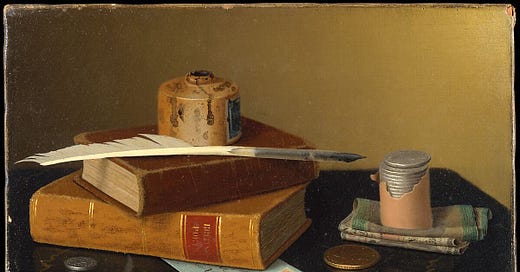

Impractically, I am trying to roll everything back and write on paper. Accordingly:

Write by hand whenever you can

I have always enjoyed writing by hand, perhaps because (1) I can write in cursive, and because (2) I have a lifelong pen fetish. I have lots of stationery and paper and Japanese pens around because they bring me joy. Things that make the heart beat faster: A blank space in an afternoon; a smooth, lightly lined page; and a 0.4mm Pilot Hi-Tec-C gel pen.

But I also increasingly write by hand because I can think better when I do.

For one, no AI monkeys are leering at me and my notebook. And for another, my brain is required to do more processing and sifting than it does when plugged in to a keyboard. My memory is keener. My patience is longer. My hand can keep up with my brain (which, admittedly, is a slow walker).

Researchers at a Norwegian university found recently what we’ve known for a while, that writing by hand ignites the brain in a powerful way that typing does not.

Tracking brain activity, the researchers found (emphasis added):

“When students wrote the words by hand, the sensors picked up widespread connectivity across many brain regions. Typing, however, led to minimal activity, if any, in the same areas. Handwriting activated connection patterns spanning visual regions, regions that receive and process sensory information and the motor cortex. The latter handles body movement and sensorimotor integration, which helps the brain use environmental inputs to inform a person’s next action.”1

We’re a bit brain dead when we’re typing. This seems hard to believe, given as much typing and texting as we all do on a daily basis.

Pushing buttons to make sentences is rather simple when compared with the necessary fine motor skills to form letters by hand.

We have to grip the pen just so, we have to light up the brain that remembers how to make the shape and what that shape means and how it relates to other shapes to form a word. There’s a lot more activity, physically and mentally, required when we write by hand. Remembering all of this gives me increased sympathy for my 5-year-old, who is studiously practicing his writing and spelling—and who still has a hard time making an “S” that curves in the right direction.

The very mechanics of writing by hand are such a boon to us now, in our screen-based world. Writing by hand opens up new avenues to my mind. I seek it now more than ever.

I’m tracking with Euclid, when he purportedly said, “Handwriting is a spiritual design, even though it appears by means of a material instrument.”

Currently reading

From Dawn to Decadence, Jacques Barzun

The Leavers, Lisa Ho

Unreasonable Hospitality, Will Guidara

The Man Who Saw Everything, Deborah Levy

Scientific American (21 February 2024)